The little patch of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) that I’ve got at the back of my garden is starting to emerge from its winter dormancy. Years ago, when I was first “bit” by this plant, I never could have imagined that one day I would grow it in my garden, or that I would be jumping up and down and clapping enthusiastically upon its first appearance each spring. Oh, how things change.

For those who have yet to experience the sting in the nettle, it may be difficult to comprehend how such a benign looking plant can be such a terrible menace, yet powerful healer rolled into one. Touching the plant creates a painful bite that radiates out from the place of contact. The pain reminds me of an ant bite. A sting may originate with your finger, but depending on the potency of the plant, you can sometimes feel its effect up into your arm. And it lingers. There have been times when I’ve felt the buzzing for hours afterward. Friends have told me stories about running through fields as children, their bare legs ravaged by contact with the plants.

My own first experience with stinging nettle was years ago while browsing books along Harbord, a street in Toronto that was once known for an abundance of quality used book shops. I have a sensory impulse towards plants and flowers that sometimes gets me into trouble. I find it especially difficult to walk past an herb without touching and then lifting my hand to my nose to take in the scent. During the growing season I must carry out this involuntary action dozens of times per day as I travel the length of my own garden, reaching, grasping, and inhaling as I move. That day on Harbord Street, I approached a cluster of herb seedlings that had been set out for sale. And, as is my way, I reached out to touch and smell the plants, almost without thinking. One plant had the textured appearance of catnip, and in one quick, involuntary action, I reached out and brushed a leaf between my fingers and quickly brought the hand up to my nose. There was no smell, but there was something else. Something foreign and surprising. “Pain! My god, the pain!” I was shocked and a little bit outraged. “What in the wha… is happening?” A quick glance at the tag and I knew this was not catnip. This was something else entirely.

Having made such a strong first impression, I was quick to do some research to learn about this demon plant and why on earth anyone would want to purchase and grow it. The first bits of info I gleaned referred to its use as a remedy for rheumatoid arthritis. Sufferers make contact between the fresh leaves and their swollen and stiffened joints to help ease the pain and swelling. [Mother Earth News has a good article about this.] I also read about how priests used it for religious rites — i.e the urtication referred to in the plant’s Latin name.

These late-season plants have started to produce flowers and seeds. They are not good for eating, but can be used to make a nutrient-rich fertilizer tea for your potted plants.

How I Grow, Harvest, and Use Stinging Nettle

Eventually, I learned that along with dandelion, chickweed, and a host of common “weeds,” stinging nettle is a fantastic dynamic accumulator, a plant that pulls nutrients and minerals up from the soil into their leaves. This makes them a powerfully nutritive spring tonic, as well as a free source of fertilizer for other plants. In the early spring I forage small quantities from wild locations as well as harvest from my own garden.

I never intended to grow nettles at home. Finding a safe, out of the way space where I wouldn’t be stung is tricky in a small, urban yard. And nettles spread. A lot. My patch got started a few years back when a volunteer appeared in the pot of a small tree I had purchased. I couldn’t toss it into the composter and ended up planting it into a small, raised bed near the back fence where there is summer shade once the tall and thick clematis vines come in. A few years later and they’ve pretty much commandeered the box. In the wild I often find nettles growing in the moist soil adjacent to waterways. I don’t have any creeks or ditches running through my urban plot, but the plant is quite adaptable and doesn’t seem to mind roadsides and wastelands as long as the soil has decent nitrogen content. I’ve had little trouble keeping it happy within the boundaries of a raised bed. I just make sure to replenish the soil each spring with a layer of compost. My friend Laurie grows it in a big pot on her roof and says that she’s had trouble with powdery mildew. I think the problem here may be that the plant’s greedy roots overgrow the pot, creating problems with air circulation, drought, and nutrient loss. My suggestion to avoid this problem is to upend the container at the end of each season and pull out the excess roots. Stinging nettle is a hardy plant so as long as the pot is not made of a breakable material, it can stay outdoors year-round.

My patch as it emerged in early spring of a previous year. Today it spans much more than a corner.

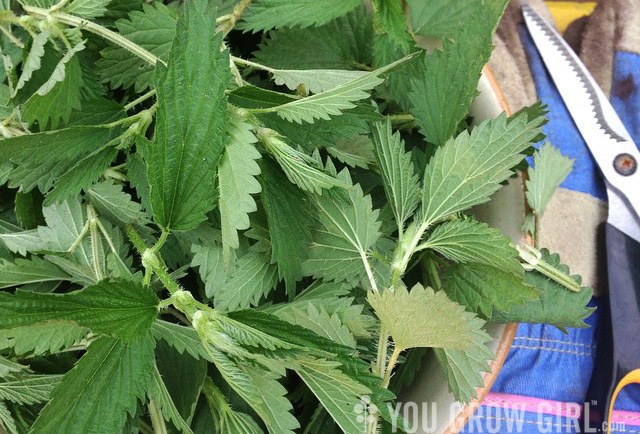

When harvesting, it is important to be aware that only the young, fresh tops are good for consumption. Older growth can irritate your urinary tract and kidneys. However, if you pinch back the new growth, you can get multiple harvests from the same plant. I recommend carrying out this procedure while wearing leather work gloves! I’ve found that regular gardening gloves will not prevent the sting from reaching your skin. A long-sleeved shirt and pants are also recommended. All it takes is one brief brush against a leaf to set off a painful reaction.

If you do get stung, there are several common plants that tend to grow nearby stinging nettle that can help alleviate the pain. What works seems to vary for each person. I always have success with plantain (Plantago). I prefer to use this plant because I have a close affinity for it. Plantain is edible (and a medicinal in its own right), so I simply pop a clean leaf into my mouth and chew it to get the juices flowing. Then I apply it to the sting. Most people swear by the crushed leaves of jewelweed (Impatiens capensis). This plant is soft and can be easily crushed between your fingers. Yellow dock (Rumex crispus) is said to work, but I’ve never tried it. Aloe gel works as well, and so does baking soda mixed with water, but you’re not likely to have one of those on hand if you’re out foraging in the back of beyond.

Back in the kitchen, I use some of the fresh leaves to make nettles soup, nettles frittata, steamed nettles, and nettles pesto (I steam the leaves first). The sting is completely removed by cooking or drying the plant. Again, leather gloves are recommended during handling. The rest is hung to dry and brewed as an herbal tea. Nettles are considered a blood purifier and tonic. It is high in iron, vitamin c, and other minerals. Nettle tea is most often often recommended for women during menstruation to help boost iron levels and prevent anemia. It is also said to have an antihistamine effect and can be drunk to help alleviate seasonal allergies.

Cutting late-season nettles back to make fertilizer tea.

I don’t let any of the plant go to waste. The hard stems are set aside and soaked in water as a compost tea, which I feed to my potted plants. I pour the sloppy, stinking plant matter that remains back into the garden. Once it has started to produce flowers, I give the patch a hard haircut, but only use this inedible plant matter to make more fertilizer tea for the garden.

To Learn More About Stinging Nettle and Its Uses: I suggest books such as Wild Food by Roger Phillips, Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild and Not-so Wild Places by Steve Brill, and Backyard Medicine by Julie-Bruton-Seal and Matthew Seal.

I had a bad experience with stinging nettles while dog walking in a large city park that has a creek running through it. It was long ago, but I think I remember urine being suggested as a way to dull the pain. Perhaps I am mistaken.

I know dunking my hand in the creek did not help at all, and the length of the walk back to the car coincided with a continuous amplification of throbbing pain.

An acquaintance uses the Stinging Nettles nutritionally, I believe in a tea. I don’t think I want them growing on my property, but it is really good to see your photos and be able to identify them.