Guest post by Beate Schwirtlich

Complete strangers step onto Bill Hulet’s patio to tell him how much they like his garden. Many of the houses on his street, which runs between downtown and a commercial strip, are rented to busy students. Until Hulet and two others bought one of those rental houses two years ago and began turning the beat-up lawn into gardens, the street was an unremarkable but convenient route for pedestrians headed downtown.

Julie Petrella lives on another bustling pedestrian route on the opposite edge of the downtown core. She is surprised by the amount of attention her garden gets from passersby.

“People actually stop and talk to you,” she says. “I think people start talking about gardens and then they do things. People are changing the way they think about their gardens.”

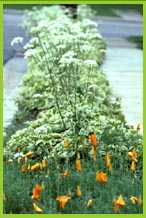

Plants like clematis, Virginia creeper and hollyhocks now thrive in the “gritty” soil along the city-owned laneway behind her house. Her tree-sheltered front yard contains shade plants, and its edge, like those of her neighbours all along the street, slants steeply down to the sidewalk. When she established what is now a lush hillside tangle of spring bulbs, roses, peonies, lilies, ivy, myrtle, sage, lavenders, and spirea, many of her neighbours were inspired to follow her lead.

The garden of Tanya Olsen, who works at Royal City Garden Centre in Guelph, Ontario, where Hulet and Petrella live, gets the same attention. She naturalized her front yard three years ago. “We were the first people on the block,” she says. “In the last two years, I’ve seen six or seven follow. We have an awful lot of people in the neighbourhood who stop by and look.”

Petrella moved from a big rural property into the city four years ago.

“We didn’t even bring a lawn mower,” she says. “I hate the noise. Our whole intention was to get rid of the thing.”

Bill Hulet, along with Mike Clancy and Mary Van Der Woude, who bought their house together as a co-op, don’t have a scrap of lawn to mow either. Even the city-owned verge is planted. His garden is ecologically minded. He composts, collects water in rain barrels and makes great use of mulch. The yard contains many native plants, such as bee balm and celedyne, as well as others put there specifically to attract birds, butterflies, wasps, bees and insects. He also makes use of vertical space, and gardens in containers on the patio, formerly the driveway. Fellow resident Van Der Woude’s garden makes use of the principles of companion planting to grow vegetables, herbs, and berries as well as annuals, flowers, and even a cactus that survived the winter in perfect form. She also makes use of her space with trellised, climbing plants, and collects rainwater.

Bill Hulet, along with Mike Clancy and Mary Van Der Woude, who bought their house together as a co-op, don’t have a scrap of lawn to mow either. Even the city-owned verge is planted. His garden is ecologically minded. He composts, collects water in rain barrels and makes great use of mulch. The yard contains many native plants, such as bee balm and celedyne, as well as others put there specifically to attract birds, butterflies, wasps, bees and insects. He also makes use of vertical space, and gardens in containers on the patio, formerly the driveway. Fellow resident Van Der Woude’s garden makes use of the principles of companion planting to grow vegetables, herbs, and berries as well as annuals, flowers, and even a cactus that survived the winter in perfect form. She also makes use of her space with trellised, climbing plants, and collects rainwater.

“It’s no secret that the lawn is an iconic image for the middle class capitalist world-view,” Hulet says. “Our yard has different plants, different textures, and is always changing. It’s harder to see that with a lawn. The idea with a lawn is to be like a billiard table. What you aim for is to minimize diversity and maximize uniformity.”

More and more people are getting rid of their lawns and naturalizing their gardens. It’s a trend that Henry Koch, interpretive horticulturist at The Arboretum, University of Guelph, sees as a reaction to “a conquest against nature, literally,” that began with the colonization of North America.

More and more people are getting rid of their lawns and naturalizing their gardens. It’s a trend that Henry Koch, interpretive horticulturist at The Arboretum, University of Guelph, sees as a reaction to “a conquest against nature, literally,” that began with the colonization of North America.

Today, Koch says, people are reacting to the absence of nature in the urban landscape. “The psyche of the new, North American post-hippie is asking “Where’s nature? What is this absurd creature we have in a lawn? What the hell’s the point of it?”

“In the late 1800’s, people had just finished clearcutting,” Koch says, a necessity to settlers who needed agricultural land and feared the both the bush and the Native American peoples who lived in it. Settlers also had a natural desire to recreate the pastoral, agricultural landscapes they’d left behind in Europe.

It was a similar desire for re-creation that brought the lawn, with a little help from the hugely influential, public-minded architect Frederic Law Olmstead, to North America during the time of the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800’s.

It was a similar desire for re-creation that brought the lawn, with a little help from the hugely influential, public-minded architect Frederic Law Olmstead, to North America during the time of the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800’s.

“The lawn of North America is inspired by the pastures of England that were grazed by sheep,” Koch explains. Frederic Law Olmstead went to England in the midst of the Industrial Revolution and visited the lush lawned private estate gardens of aristocracy. At the same time, Olmstead observed the difficult living and working conditions of the Revolution in both England and North America.

“Olmstead returned to America and persuaded the ‘chiefs’ of New York to have a public–not private–park, to provide relief from the working conditions of the Industrial Revolution,” Koch says.

Central Park, echoing the gardens of aristocracy but serving the people, was built, while, at the same time, the lawn mower was invented. Then Olmstead went on to design more parks and America’s first suburb, ‘Riverside’ in Chicago. Incorporated into its design was the ‘thirty foot set-back’ of houses from the road. Blanketing that expanse from house to sidewalk were and are–park-like lawns.

Today it’s common knowledge that the conquest against nature has been all too successful. Koch thinks naturalization is partly a response to growing concern about the environment. “We’re looking at the world around us, and we read daily the horror story of species extinction, pollution, the horror story of the environment.”

Today it’s common knowledge that the conquest against nature has been all too successful. Koch thinks naturalization is partly a response to growing concern about the environment. “We’re looking at the world around us, and we read daily the horror story of species extinction, pollution, the horror story of the environment.”

Gardens are places for “the daily experience of natural relationships,” Koch says, while lawns or brief yearly vacations ‘into’ nature aren’t. “The whole garden becomes a story. It’s full of surprises.”

“We no longer see that we are the all important thing in creation. It’s got a being of its own.”

Tanya Olsen has helped many people plan naturalized gardens. “People are looking for tranquility,” she says. “They want to come home and leave the chaos of work. The garden becomes an extension of living space. ”

Tanya Olsen has helped many people plan naturalized gardens. “People are looking for tranquility,” she says. “They want to come home and leave the chaos of work. The garden becomes an extension of living space. ”

She attributes part of their popularity to the past recession that had people travelling less and spending more time at home: she says that people visit the garden centre wanting to build gardens and patios instead of buying cottages.

In her experience, though, it’s sometimes more a matter of pride in property. “People are taking more and more pride in their houses,” she says, “and I guess a lot of people out there have to one-up their neighbours.”

“A nice garden, or anything that makes people say — I have to have — will make a house sell faster, though it hasn’t contributed to property value up to now.” says Guelph real estate agent Helen Kusserow. “Eventually that will come but we’re not there yet.”

Olsen and Koch agree that native plants are very popular these days alongside time-tested garden favourites. But as a horticulturist, Koch thinks the impact of a naturalized garden is equivalent–for creatures and people alike whether filled with native plants or exotic botanical specimens.

At the same time, he acknowledges that gardens are “artificial botanical zoos, a far cry from nature” that condense a geographical diversity of plants into a small space. “Wildlife functions in relation to the structure of landscape. Birds don’t give a damn whether the structure came from Europe or North America. ” Where lawns demand routine, joyless (to most people) maintenance, gardens demand imagination. “I want to go outside and putter and you can’t go out and putter with a lawn mower.” says Petrella of the work she does in her “English-style” garden.

Hulet feels that lawns are about conformity and control. “Your head manifests itself in your lawn,” he says. With his garden, Hulet aims for just the opposite. “It’s about teaching yourself to see subtleties and respect the world of difference,” he says.

Hulet feels that lawns are about conformity and control. “Your head manifests itself in your lawn,” he says. With his garden, Hulet aims for just the opposite. “It’s about teaching yourself to see subtleties and respect the world of difference,” he says.

Likewise, Koch wouldn’t want to impose a garden ideal or icon. “Some people do their gardens neat, some people let it roll. Diversity is inherent to nature, we’re part of nature Thank goodness there’s diversity.”

As Petrella, surveying her street, observes, “Those green corners are going.” Like hers, and Hulet’s, over on the other side of downtown, many others in many cities have already gone.