I have long sung the praises of the perpetual aka perennial onion. Allow a few to multiply each year and you will have them forever.

I started growing one such type, ‘Egyptian Walking’ onion (Allium proliferum) aka tree onion in my community garden plot well over a decade ago. The exact date is a lost memory to me now as is how I came by it in the first place, but I suspect that I may have been growing from the same stock for approaching 18 years. In that time I have passed on countless full-sized onions and bulbils (the small bulbs that form at the top of mature plants) to friends and neighbours without making the slightest dent in my own yearly harvest.

The work involved in growing this particular crop is about as simple as it gets. I toss the bulbils into empty spaces around the garden in the fall and start harvesting them in the spring from spots that are needed for planting other crops. I continue harvesting through the season, always making sure to let some mature and produce more bulbils. So many years and gardens later and I still have some growing at my community plot completely hands off. All I have to do is show up there twice a season to collect the bounty. No watering, fertilizing, or planting required.

Perpetual onions are pretty much free food. Why isn’t everyone growing them?

For some time now I was under the mistaken impression that I had learned everything there was to know about perennial and multiplier onions and that I had tried them all. However, on my recent trip to Arizona I was shocked to discover something I had never heard of before! I found it while perusing the Native Seeds/SEARCH catalogue shortly before visiting their Tucson, Arizona shop. While the aforementioned perpetual onions are adapted to cold climates and can survive the winter months in the ground, ‘Tohono O’odham I’itoi’ is especially suited to the dry Sonoran low-desert climate where they go dormant through the hot and arid summer months and come alive with the rainy seasons.

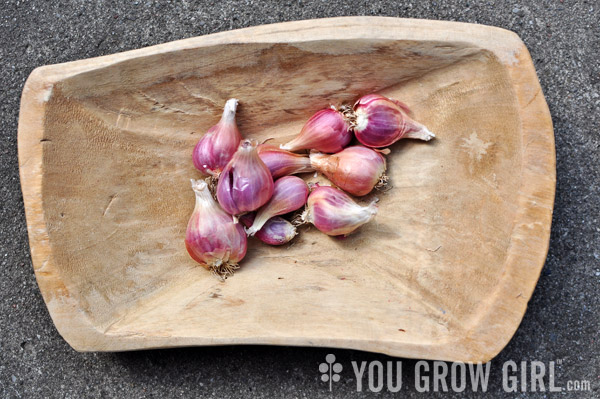

While this particular onion is named for the creator deity of the Tohono O’odham people, it is suspected that it was brought to the US by Jesuit missionaries in the late 17th century and is a very old precursor to the cultivated shallots we grow today.

The bulbs are very shallot-like, mulipliers (Allium cepa var. aggregatum), which means that they propagate themselves by bulb division underneath the ground rather than from top-setting bulbils like my beloved ‘Egyptian Walking.’ [Note that Native Seeds/SEARCH has them listed simply as Allium sp. and does not identify them with the multipliers botanically.]I am yet to taste it as I am saving the small packet I bought to grow out in the garden; however, the taste is described as bold and peppery.

At this time I am concerned about where and when to start the bulbs in my own Northern garden. My best guess is that they should not be planted in my raised beds but might be better suited to the dryer, sandy(ish) soil that dominates the rest of the yard. While I think they would do fine in the raised beds, my fear is that they will not overwinter well there. My plan is to put them all out now to grow out through the summer months, and then transplant a few into pots come fall, which I will overwinter in my unheated porch where they will be protected from prolonged freezes. I may also try pulling a few and storing them somewhere dry and dark out of soil. In terms of when to start, I fear that early spring was the right time since that is when I start my shallots. However, I have bulbs now and it is highly unlikely that I will be able to keep them viable out of the soil until next spring. For that reason I am going to plant them now and try my luck.

Have you grown this onion? What do you think of it?

Wow, so interesting! Now I want to give perpetual onions a try. Good luck with your new (ancient) onion.

Do it! Onions forever.

I’ve been growing the Egyptian variety for a few years, but mostly forgetting about them till it was too late to pick and use them. This year we had tons *and* we realized it while they were still good. So we sliced up and dried them to use after we pick and use all the walla wallas. Yay!